Recently, I received an email “out of the blue” directly from Ofsted inviting me to their head office for “a round table discussion on Ofsted’s new inspection framework, with Amanda Spielman.” I had no idea why I’d been invited but naturally, with curiosity getting the better of me, I accepted the invitation.

On arriving at the Ministry of Justice building where the Ofsted HQ is housed, let’s just say that the security system was unlike anything else I’d experienced. At one point, I thought I was going to be teleported somewhere a la Star Trek! It turned out that fifteen of us had been invited, so we set about trying to find out what either we as individuals or our schools had in common. Clearly, there was no Sherlock Holmes amongst us as all we could ascertain was that our schools were all in London.

On meeting Amanda Spielman, one thing that struck me was that she did have the presence of a class teacher even though she’d never been one. As such, a few weeks after this event, I’m left to own up to my prejudice and reservation about her initial appointment. Another factor that became immediately apparent is that she is sharply focused on making sure that excellent provision and practice should be evidenced strongly across the nation and not just in certain regions. We listened to her talk about curriculum issues for just under ten minutes before she opened up the discussion for our contributions.

One point I made is that within Ofsted HQ, they should never underestimate their power and influence, particularly over leaders who are more concerned with acting upon direction rather than forging their own vision. If Ofsted put out a report stating that a goldfish pond in the middle of a school playground raised attainment in boys’ writing or closed the attainment gap for the disadvantaged, there would be those head teachers who’d immediately dispatch their site manager into the playground with a kango hammer whilst sending an office junior to the local pet shop without giving it a second thought!

In my view, Ms Spielman is entirely right to focus on the curriculum. With my dad hat on, I think it’s ridiculous that my daughter’s formal geography education is over at fourteen years of age, just to make room for triple science and, of all things, citizenship. At primary level, the number of schools that never engage in a full on dramatic production for their pupils at any stage within their primary education is alarming. So Ofsted, I’m right with you on this…but I’m nervous.

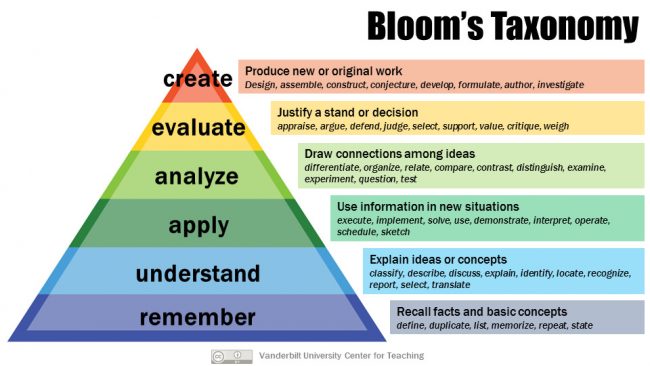

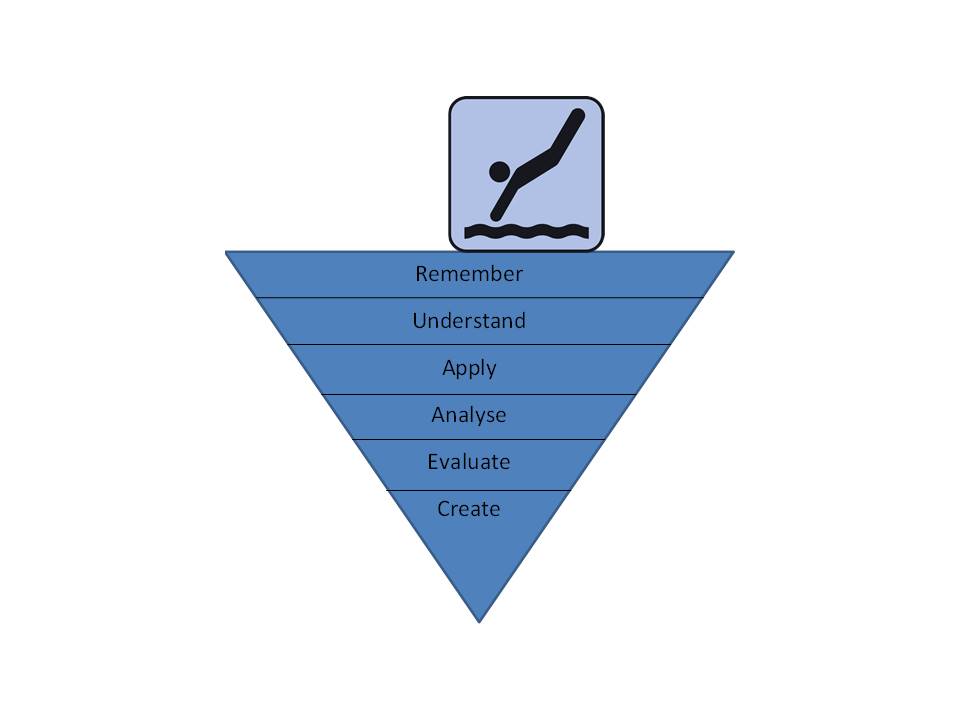

Since the headlines broke that curriculum provision is going to form a prominent part of the new framework, the school I lead (St Leonard’s Church of England Primary in Streatham, London) has received an increasing number of requests for visits from interested senior leaders. At St Leonard’s we teach and learn through the International Primary Curriculum (IPC). We’ve done so since 2012 and are now one of IPC’s few “accredited schools”. We chose this curriculum because we strongly believe in developing knowledge, skills and understanding in many subjects, giving all children, with their different gifts and talents, a chance to succeed. Our curriculum is underpinned by an established learning policy created by different stakeholders within the school community. It is now matched with an assessment policy bringing meaningful assessment to foundation subjects. I write this not so much to promote the IPC (although I thoroughly recommend it) but to make the point that to develop a rich curriculum that is as robust as it is diverse takes time – and there will be those school leaders who are not going to be prepared to wait, because they are either going to be acting in fear or, even worse, trying to rapidly establish a personally successful reputation so that they can move on with personal ambition.

One visitor to our school had been sent by their head teacher to look at our provision. However, what quickly became evident was that they’d been sent to evaluate a product to see if it could be used as an additional bolt-on to what they currently offered. The curriculum should be no different from any other aspect of school leadership. It needs to be based upon a clear vision, rooted in philosophy and pedagogy, and resourced adequately to promote the best possible outcomes. If school leaders think that their curriculum can merely be tinkered with to give the impression that it’s more holistic, they are doomed to failure. Moreover, if they think that what in effect is window dressing will not be identified in an inspection, they are incredibly naïve. My worry is that enough school leaders will simply chuck a few “interesting topics” in and have one off artistic visitors to try and give the impression of a broad and balanced curriculum. This of course will fail dismally and, when it does, some will use the data as evidence that broad and balanced doesn’t work.

One of the school leaders present at the discussion summed everything up beautifully by simply stating, “When all is said and done, it’s about brave leadership.”

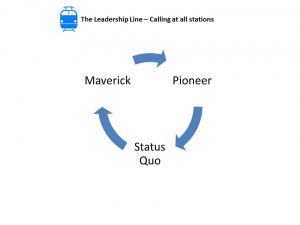

I’ve often said to my colleagues that, over a decade, I’ll go through a reputational cycle. For a few years I’ll be considered a maverick, for a few years I’ll be considered a pioneer and for a few years I’ll be considered as maintaining the status quo. Therein lies the importance of having a clear vision and philosophy for success that can withstand the winds of change.

For me, the foundation subjects are to be understood as exactly that. The brilliant cellist Yo-Yo Ma in an interview with Andrew Marr stated that, as a young man, he was simply fighting for the arts to have “a place at the table”. However as he became older, he “realised that the arts were the table.” I was really struck by this analogy. At a time when we are at risk of losing expertise and participation in so many subjects, Ofsted are currently on the right path and we should see this as an opportunity to make a successful journey along it. For this to happen, it is vital that Ofsted recognise and endorse this as an evolutionary process; that, as professionals, our “table” is thoughtfully and expertly crafted over time – and that every child has a seat at it.

Best wishes,

Simon Jackson

Andy Buck in his book, Leadership Matters, refers to the importance of culture and climate. Often, the first few days and weeks in September can define these characteristics for the entire school year.

Andy Buck in his book, Leadership Matters, refers to the importance of culture and climate. Often, the first few days and weeks in September can define these characteristics for the entire school year.