When it comes to education, its importance is underlined by the fact that most people hold such passionate opinions about it. Whether it’s the curriculum – what it contains and how it’s taught, ability or mixed ability grouping, the importance and amount of homework, assessment and testing, marking and feedback; the list seems endless.

When it comes to education, its importance is underlined by the fact that most people hold such passionate opinions about it. Whether it’s the curriculum – what it contains and how it’s taught, ability or mixed ability grouping, the importance and amount of homework, assessment and testing, marking and feedback; the list seems endless.

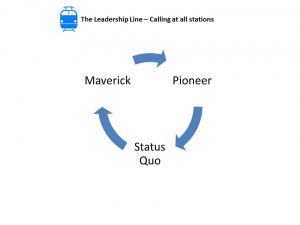

In relation to my own views, some of which I’ve held throughout my twenty five years as a teacher, others which I’ve arrived at as a result of experience, I’ve come to the conclusion that, if you’re a principle centred school leader, you’re aboard a train on a cyclical journey with three stations – “Status Quo”, “Maverick” and “Pioneer”.

For example, when I started teaching, performance assemblies and various productions in schools were commonplace (the status quo). Then, armed with a variety of excuses, such events were seen by many school leaders as time consuming and that the increased requirements of the curriculum did not allow for them. As such, those of us who believe that the expressive arts should be at the heart of many things and not just education, were considered as mavericks and that we would soon pay for our folly. As a head teacher, providing education with high quality arts and humanities opportunities at its core has been non- negotiable for me. As such, I’ve led a school with a team of staff and governors committed to providing the broad and balanced curriculum irrespective of the status quo. Fast forward to Ofsted’s welcome announcement that schools will be judged in part according to the curriculum on offer and, “Ding ding; welcome to Pioneer. All aboard!”

It is my view that we have to break such cycles because progress should be about discovery and advancement, not going round in circles. However, for that to happen, we need to be clear as to how such cycles can be avoided.

Firstly, there is a duty upon school leaders to have the courage to stay true to their principles and remain resilient when facing pressure to adopt the latest trend (NB: this does not mean being intransigent or ignoring substantial, credible evidence identifying reasons for change).

Secondly, there is a duty of government not to become obsessed with trying to climb international league tables. Remember, in a rat race, even the winner is a rat! (Are you reading, Russia?) If they wish to improve the quality of education, then there needs to be consideration and genuine consultation as to what is likely to create such improvement and how this can be best achieved. Underpinning this should be a genuine understanding that the timeline for progress should not be aligned with party politics or the calendar of the electoral process. I have been fortunate enough to visit schools in other countries. I’ve seen some practice which has provided opportunities for me to positively reflect on provision within my own school. However, I’ve also seen a lot of stuff which, not to put too fine a point on it, has been horrifying – some of which has happened in countries with better international league table positions than England.

Thirdly, supposedly independent bodies should act as such. There are a host of civil servants engaged in delivering policy without seemingly having any understanding of why they are doing it other than obeying their political masters / mistresses. Similarly, the leadership and management structure of the inspectorate needs to reflect the vast expanse that is the world of education. For example, the National Director of Education was recently at pains to point out that he “commended” the contents of the Early Years “Bold Beginnings” document. Well, when one’s own experience is senior leadership within secondary education, one doesn’t have much option but to accept on trust what’s been produced!

Recently I’ve watched the resurgence of the debate around marking and feedback. Cue another cyclical storm which will provide opportunities for some schools to implement oppressive and unrealistic policies, others to abdicate from marking altogether and, somewhere in the middle, companies and consultants making shed loads of cash out of the confusion.

Surely it’s reasonable to say that policy and practice should reflect principle?As such, I invite you to reflect on the following questions:

- How can the teacher ensure that there’s appropriate purpose behind a child’s work?

- How can the teacher ensure that a child knows that they have high expectations of them?

- How can the teacher make a child feel that they care about their individual progress and development?

- How can the teacher best obtain clear knowledge about what a child can and can’t do or understand?

- How might marking contribute to delivering answers to the above questions?

- What other practice might make a valuable contribution?

- How might manageable marking support outstanding teaching and learning in your school?

I’ve always considered marking as part of our duty of care, guidance and support (CGS). So momentarily writing as a parent, the impression I’ve received is that whilst secondary schools often provide excellent CGS in relation to general well-being, pastoral care and personal advice, there is far less evidence that the subject teacher actually provides CGS in relation to the student’s work, especially when compared with primary practice.

So, in conclusion, I invite us all not to jump on the latest marking / not marking train. Let’s not be labelled as maintaining the status quo, mavericks or pioneers. Let’s genuinely consult and reflect on impartial evidence whilst remembering Dylan William’s observation: The question is not, “What works?” because everything works somewhere. The question is, “What works here?”– understanding that “here” might mean England, an education age phase or indeed a school.

This blog terminates here. All change please!

Simon Jackson